It is almost twenty years since I last spoke at an archaeological conference. There was a time when I would present papers (sometimes in English, sometimes in French) at six or more of these conferences in the course of a year, but then I moved on to other things: politics in the mid 1990's; academic leadership in the first nine years of this century; writing novels since 2009. It came as something of a surprise, therefore, to be invited to speak at the 25th Theoretical Roman Archaeology Conference at the University of Leicester, this past weekend.

I was asked to talk about the process of researching and writing my novel, An Accidental King (a fictionalised autobiography of the pro-Roman British client king, Tiberius Claudius Cogidubnus), and to address the question as to whether fiction can be "an aid to research" into the ancient world.

Archaeologists make use of many theoretical models, but the first one I was introduced to, as an undergraduate, was the "ladder of inference" of Professor Christopher Hawkes: the idea being that it is relatively easy for an archaeologist to make inferences about ancient technology (we observe it directly), somewhat less easy to make inferences about ancient economies (we have animal bones and plant remains, but many other materials have decayed), and much more difficult to make inferences about social systems or religious beliefs in the remote past. Since these were precisely the things I was most interested in, I spent the best part of fifteen years teetering slightly uneasily on the top rungs of the unsteady metaphorical ladder.

Roman mosaic from Merida, Spain (image is in the Public Domain).

When it came to writing fiction, I was always clear that the enterprise was a literary, not an archaeological one, and yet there were more similarities, perhaps, than I expected to find. As an archaeologist, I pursued my research objectives through "fieldwork." As a novelist, too, I found it necessary to get out there into the landscape: around Chichester Harbour, which I tried to see both through the eyes of Cogidubnus himself, who must have grown up there, and through the eyes of a Roman commander planning an invasion; in Rome, where I walked the route of Claudius's British Triumph; and in Norfolk, where I tried to imagine the ways in which the Boudiccan Revolt might actually have been played out, day by day, conversation by conversation.

Chichester Harbour. Photo: John Armagh (licensed under CCA).

I recall this advice from Dame Hilary Mantel: "One challenge a writer of historical fiction has is to stay with your character in the present moment, and not be seduced by hindsight - zipping to the end of the process, from where you can pass judgement." This is precisely what I tried to do in the course of my literary "fieldwork." Fieldwork, however, is never the end of the research process: just as an archaeologist moves from the field into the laboratory to study the objects that have been retrieved from an excavation, so the novelist has to process and refine the thoughts and ideas noted down in the landscape.

Thetford Castle, Norfolk. Photo: Ziko-C (image is in the Public Domain).

There were some things that I found hard to imagine, and here I sought insights in places that an archaeologist would rarely look. An archaeologist stands, in Mantel's terms, at the end of the process. We know from the historical sources that London, Colchester and St Albans were burned in Boudicca's revolt; we can see the evidence for this in physical layers of burned material in excavations in these cities; we know that her forces were subsequently defeated by the Roman Governor, Suetonius Paulinus, and that she was either killed, or committed suicide. We see the outcomes, but almost nothing of the process. In trying to imagine this process, I read eyewitness accounts of modern conflicts (Bosnia, Rwanda), and spoke to people (journalists, soldiers, refugees) who had been on the ground.

"Speculation may wander over its wide and spacious domain," wrote the 19th Century antiquarian, Sir Richard Colt-Hoare, despairing over the archaeology of his native Wiltshire, "but it will never bring home with it either truth or understanding." Do fictional explorations of the past carry truth or understanding that science alone cannot provide, or do they merely add layers of obfuscation? There is no simple answer. Certainly I write my novels as contributions to literature, not archaeology or history, but I am engaging with the same material past that I previously studied as an archaeologist.

At the weekend's conference at Leicester, archaeologists and classicists (Rob Witcher of the University of Durham, Daan Van Helden of the University of Leicester, Joanna Paul of The Open University) came together with a story-teller (Michael Given of the University of Glasgow, who told a story of a remarkable encounter in Cyprus) and novelists (V.M. Whitworth of the University of the highlands and Islands, as well as myself) to consider these questions. I hope that it will be the first of many such conversations.

Mark Patton's novels, Undreamed Shores, An Accidental King and Omphalos, are published by Crooked Cat Publications, and can be purchased from Amazon UK or Amazon USA.

Monday 30 March 2015

Wednesday 25 March 2015

Codex Callixtinus: The Forged Document that Changed Medieval Europe

In an earlier blog-post, I explored the emergence and development of the Medieval cult of Saint James at Compostela. The cult has its origins in the 9th Century, but it would not have developed into the international pilgrimage phenomenon that was "The Way of Saint James," were it not for a 12th Century document signed in the name of Pope Callixtus II (1065-1124). The document, however, is a forgery, written at least a decade after Callixtus's death.

Callixtus II, Pope from 1119 to 1124 (image is in the Public Domain).

Illustration of the Apostle James, from the original copy of the Codex Callixtinus, in the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela (image is in the Public Domain).

The Codex Callixtinus, or Liber Sancti Jacobi, the original copy of which is held by the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela (it was stolen in 2011, but recovered a year later), and was probably written between 1135 and 1145. One of its authors appears to have been a French cleric by the name of Aymeric Picard. It consists of five books which, between them, define aspects of the cult of Saint James, making this the best documented of all Medieval pilgrimage cults.

1. The Book of the Liturgies, including a sermon, supposedly written by Callixtus, to be preached to pilgrims, as well as some of the earliest surviving liturgical music.

2. The Book of the Miracles, documenting the miracles performed by Saint James at the shrine of Compostela.

3. The Transfer of the Body to Santiago, an account of the miraculous translation of Saint James from the Holy Land to Compostela.

4. The History of Charlemagne and Roland, a heavily mythologised account of their battles in Spain, explicitly linking them to the cult.

5. A Guide for the Traveller, a practical guide to the principal routes through France and Spain to Compostela.

Illustration of Charlemagne and his knights on the road to Compostela, from the original copy of the Codex Callixtinus (image is in the Public Domain).

It is known that a copy was made in 1173 by a monk, Arnaldo de Monte (this copy is now in Barcelona), and it is likely that other copies were held in various monastic houses around Europe. It is unlikely that pilgrims actually carried copies of the travellers' guide on the road (manuscripts hand-written on vellum were both expensive and delicate). Canons from the monastic houses probably studied the documents in their own scriptorums, and then acted as guides.

This, however, leaves open the question as to who was responsible for the forgery. Aymeric Picaud may have researched the travellers' guide, but he is surely too obscure a figure to have contrived the entire enterprise on his own. A clue may be found in the dedication of the opening letter, supposedly written by the Pope: it is addressed to "The holy assembly of the Basilica of Cluny, and Diego, Archbishop of Compostela."

Nobody had more to gain from the enterprise than Archbishop Diego Gelmirez and his See, so he can hardly be free from suspicion. It is interesting that, among the great innovators of the Medieval Church, he stands out as a figure who was never canonised, so perhaps this suspicion weighed heavily in the balance.

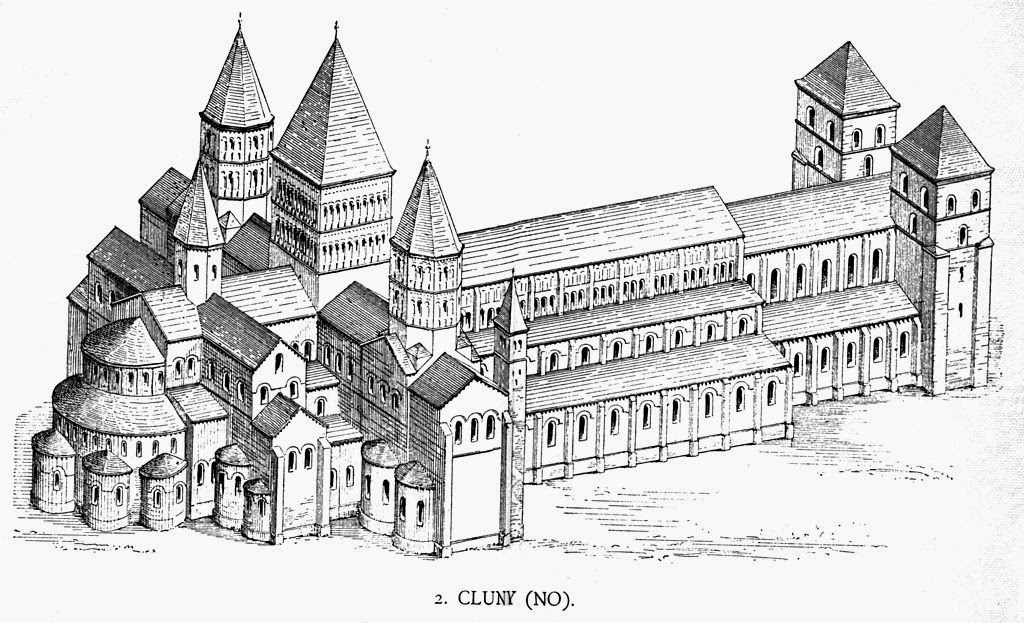

Reconstruction of the Medieval Abbey of Cluny, by Georg Delvio & Gustav von Bezold (image is in the Public Domain).

The Abbey of Cluny, in Burgundy, was perhaps the wealthiest monastic house of its time, its abbot answerable only to the Pope. This abbot, at the time, was Peter the Venerable, another leading churchman who was never formally canonised, although he has sometimes been honoured as if he were a saint.

Peter the Venerable, with three of his monks. 13th Century Manuscript, Bibliotheque Nationale de France (image is in the Public Domain).

Peter was, by the standards of his day, an ecclesiastical moderate: he had travelled in Spain, conversing with Islamic scholars; and commissioned the first Latin translation of the Koran. His commentary identified Islam as a "heresy," but he did not condemn it without first seeking to understand it. Peter the Venerable also gave sanctuary to the theologian, Peter Abelard, after he had been condemned by Bernard of Clairvaux. Might he, then, as Bernard preached the Second Crusade, have conspired with Diego Gelmirez to send pilgrims in the opposite direction, both geographically and spiritually, on the peaceful road to Compostela? We may never know the full truth, but the "Way of Saint James" would long outlive both Diego Gelmirez and Peter the Venerable, and provide a model for the development of later pilgrimage cults, including that of Saint Thomas a Becket at Canterbury.

Mark Patton's novels, Undreamed Shores, An Accidental King and Omphalos, are published by Crooked Cat Publications, and can be purchased from Amazon UK or Amazon USA.

Callixtus II, Pope from 1119 to 1124 (image is in the Public Domain).

Illustration of the Apostle James, from the original copy of the Codex Callixtinus, in the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela (image is in the Public Domain).

The Codex Callixtinus, or Liber Sancti Jacobi, the original copy of which is held by the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela (it was stolen in 2011, but recovered a year later), and was probably written between 1135 and 1145. One of its authors appears to have been a French cleric by the name of Aymeric Picard. It consists of five books which, between them, define aspects of the cult of Saint James, making this the best documented of all Medieval pilgrimage cults.

1. The Book of the Liturgies, including a sermon, supposedly written by Callixtus, to be preached to pilgrims, as well as some of the earliest surviving liturgical music.

2. The Book of the Miracles, documenting the miracles performed by Saint James at the shrine of Compostela.

3. The Transfer of the Body to Santiago, an account of the miraculous translation of Saint James from the Holy Land to Compostela.

4. The History of Charlemagne and Roland, a heavily mythologised account of their battles in Spain, explicitly linking them to the cult.

5. A Guide for the Traveller, a practical guide to the principal routes through France and Spain to Compostela.

Illustration of Charlemagne and his knights on the road to Compostela, from the original copy of the Codex Callixtinus (image is in the Public Domain).

It is known that a copy was made in 1173 by a monk, Arnaldo de Monte (this copy is now in Barcelona), and it is likely that other copies were held in various monastic houses around Europe. It is unlikely that pilgrims actually carried copies of the travellers' guide on the road (manuscripts hand-written on vellum were both expensive and delicate). Canons from the monastic houses probably studied the documents in their own scriptorums, and then acted as guides.

This, however, leaves open the question as to who was responsible for the forgery. Aymeric Picaud may have researched the travellers' guide, but he is surely too obscure a figure to have contrived the entire enterprise on his own. A clue may be found in the dedication of the opening letter, supposedly written by the Pope: it is addressed to "The holy assembly of the Basilica of Cluny, and Diego, Archbishop of Compostela."

Nobody had more to gain from the enterprise than Archbishop Diego Gelmirez and his See, so he can hardly be free from suspicion. It is interesting that, among the great innovators of the Medieval Church, he stands out as a figure who was never canonised, so perhaps this suspicion weighed heavily in the balance.

Reconstruction of the Medieval Abbey of Cluny, by Georg Delvio & Gustav von Bezold (image is in the Public Domain).

The Abbey of Cluny, in Burgundy, was perhaps the wealthiest monastic house of its time, its abbot answerable only to the Pope. This abbot, at the time, was Peter the Venerable, another leading churchman who was never formally canonised, although he has sometimes been honoured as if he were a saint.

Peter the Venerable, with three of his monks. 13th Century Manuscript, Bibliotheque Nationale de France (image is in the Public Domain).

Peter was, by the standards of his day, an ecclesiastical moderate: he had travelled in Spain, conversing with Islamic scholars; and commissioned the first Latin translation of the Koran. His commentary identified Islam as a "heresy," but he did not condemn it without first seeking to understand it. Peter the Venerable also gave sanctuary to the theologian, Peter Abelard, after he had been condemned by Bernard of Clairvaux. Might he, then, as Bernard preached the Second Crusade, have conspired with Diego Gelmirez to send pilgrims in the opposite direction, both geographically and spiritually, on the peaceful road to Compostela? We may never know the full truth, but the "Way of Saint James" would long outlive both Diego Gelmirez and Peter the Venerable, and provide a model for the development of later pilgrimage cults, including that of Saint Thomas a Becket at Canterbury.

Mark Patton's novels, Undreamed Shores, An Accidental King and Omphalos, are published by Crooked Cat Publications, and can be purchased from Amazon UK or Amazon USA.

Thursday 19 March 2015

A History of the World in 50 Novels. 24 "From the Mouth of the Whale," by Sjon

A history of the world ought not only to recount the deeds of great men and women, or the events that took place in and between the great cities of the world's continents. There have always been people living at the margins of the known world, with one eye looking out for a ship arriving from a distant port, and the other gazing out at nature in her most beautiful (because unspoiled), but also her most savage (because untamed) countenance.

Three Icelandic Landscapes, by Fran Cano Cabal (licensed under CCA).

The 17th Century was a dismal age in which to be an Icelander. The islanders had to contend with the plagues that were ravaging the whole of Europe, and with the volcanic eruptions that have always been a feature of Icelandic life, but they were also subject to foreign domination, that of Denmark.

Over the course of the previous century, the Lutheran Reformation had been imposed on Iceland by the Danish Crown by force, and now, in 1602, Denmark imposed a trade monopoly on Iceland, forbidding the islanders from trading with the merchants of any land except Denmark, whose king would fix the prices (they has previously made a precarious living by trading salted cod and homespun wool with English and Hanseatic merchants).

Iceland, from the Carta Marina of Olaus Magnus (image is in the Public Domain).

The threat of starvation was a real one, and, in this context, neighbour was frequently set against neighbour in disputes that could, in theory, be about almost anything, but which, ultimately, were about access to the few resources on which survival depended.

From the Mouth of the Whale, by the Icelandic poet, Sjon, tells the story of Jonas Palmason, known as "the Learned:" a recusant Catholic, self-educated healer, would-be alchemist and scholar of the natural world. Following a dispute, in which he has been accused of sorcery, he is banished to remote Gullbjorn's Island. Eventually his wife is allowed to join him (or does he imagine this), and later, a ship arrives to take him (but not his wife) to Copenhagen (or is he dreaming), where Ole Worm, the leading Danish intellectual of the day, will plead his case before King Christian IV. But will the king agree to commute his sentence, allowing him to continue the scientific work he has begun with Worm, or send him back out into the wilderness?

Ole Worm, physician to King Christian IV, linguistic scholar and natural scientist, by J.P. Traps (image is in the Public Domain).

Worm's Cabinet of Curiosities, a forerunner of the modern museum, but also a laboratory, which features in the novel (image is in the Public Domain).

I first read this novel as I was writing my own Undreamed Shores, and only realised on re-reading it just how profoundly it had influenced my own writing. There are many things I love about it. It is, in part, a love poem to the Icelandic landscape, which Jonas has plenty of time to meditate upon. Since they are his only companions, he can hardly fail to notice the birds, who become characters in their own right. It is a historical novel in which the boundaries between the historical and the fictional dissolve (Ole Worm is certainly a historical character, but what about Jonas? The truth is probably accessible only to someone who can read Icelandic), as do the boundaries between Jonas's material world and his life of the mind. It is written with a poet's sensitivity, gloriously rendered in Victoria Cribb's English translation. In short, it is as completely immersive as any historical fiction can ever be, and that gave me something to aspire to as I made my first steps towards publication.

"A medium-sized fellow ... Beady brown eyes set close to his beak within pale surrounds ... The beak itself quite long, thick and powerful, with a slight downward curve at the end, dark in colour, but lighter at the top ... clad in a grey-brown coat of narrow cut, with a faint purple sheen in the twilight ... importunate with his own kind, garrulous with others ... so one might describe the purple sandpiper, and so men describe me ... I can think of many things worse than being likened to you, my feathered Jeremiah, for we have both crawled from the hand of the same craftsman, been carved with the same knife: you quickened to life on the fourth day, I on the sixth ... But what if the order had been reversed?"

Purple sandpiper (Calidris maritima). Photo: Ron Knight (licensed under CCA).

"The island rises ... it emerges from the deep as the flood tide strips the water from its shores ... Fish flee the dry land, out to the dark depths ... Shore birds, newly arrived, follow the ebbing tide, scurrying along the water's edge, pecking around their feet ... The tide mark retreats rapidly, like a silk glove drawn off a maiden's hand ... A bank of liver-coloured seaweed glitters in the morning sun, swollen and vulnerable ... Ever more is revealed of the black bedrock on which the island sits."

"The days now passed in discourse of runes and old Icelandic poetry. Ole Worm placed many riddles before Jonas on the Eddic and Skaldic compilations of Snorri Sturluson, which he was able to answer straight off ... But the university rector had other duties to attend to besides tapping Jonas's wisdom, and this gave the latter the chance to observe the work in Worm's collection of natural history and curiosities, known as the Museum Wormianum ... An elite team of the rector's students was busy cataloguing the collection ... Here Jonas set eyes for the first time on many marvels he had hitherto only read about in books ... "

Mark Patton's novels, Undreamed Shores, An Accidental King and Omphalos, are published by Crooked Cat Publications, and can be purchased from Amazon UK or Amazon USA.

Three Icelandic Landscapes, by Fran Cano Cabal (licensed under CCA).

The 17th Century was a dismal age in which to be an Icelander. The islanders had to contend with the plagues that were ravaging the whole of Europe, and with the volcanic eruptions that have always been a feature of Icelandic life, but they were also subject to foreign domination, that of Denmark.

Over the course of the previous century, the Lutheran Reformation had been imposed on Iceland by the Danish Crown by force, and now, in 1602, Denmark imposed a trade monopoly on Iceland, forbidding the islanders from trading with the merchants of any land except Denmark, whose king would fix the prices (they has previously made a precarious living by trading salted cod and homespun wool with English and Hanseatic merchants).

Iceland, from the Carta Marina of Olaus Magnus (image is in the Public Domain).

The threat of starvation was a real one, and, in this context, neighbour was frequently set against neighbour in disputes that could, in theory, be about almost anything, but which, ultimately, were about access to the few resources on which survival depended.

From the Mouth of the Whale, by the Icelandic poet, Sjon, tells the story of Jonas Palmason, known as "the Learned:" a recusant Catholic, self-educated healer, would-be alchemist and scholar of the natural world. Following a dispute, in which he has been accused of sorcery, he is banished to remote Gullbjorn's Island. Eventually his wife is allowed to join him (or does he imagine this), and later, a ship arrives to take him (but not his wife) to Copenhagen (or is he dreaming), where Ole Worm, the leading Danish intellectual of the day, will plead his case before King Christian IV. But will the king agree to commute his sentence, allowing him to continue the scientific work he has begun with Worm, or send him back out into the wilderness?

Ole Worm, physician to King Christian IV, linguistic scholar and natural scientist, by J.P. Traps (image is in the Public Domain).

Worm's Cabinet of Curiosities, a forerunner of the modern museum, but also a laboratory, which features in the novel (image is in the Public Domain).

I first read this novel as I was writing my own Undreamed Shores, and only realised on re-reading it just how profoundly it had influenced my own writing. There are many things I love about it. It is, in part, a love poem to the Icelandic landscape, which Jonas has plenty of time to meditate upon. Since they are his only companions, he can hardly fail to notice the birds, who become characters in their own right. It is a historical novel in which the boundaries between the historical and the fictional dissolve (Ole Worm is certainly a historical character, but what about Jonas? The truth is probably accessible only to someone who can read Icelandic), as do the boundaries between Jonas's material world and his life of the mind. It is written with a poet's sensitivity, gloriously rendered in Victoria Cribb's English translation. In short, it is as completely immersive as any historical fiction can ever be, and that gave me something to aspire to as I made my first steps towards publication.

"A medium-sized fellow ... Beady brown eyes set close to his beak within pale surrounds ... The beak itself quite long, thick and powerful, with a slight downward curve at the end, dark in colour, but lighter at the top ... clad in a grey-brown coat of narrow cut, with a faint purple sheen in the twilight ... importunate with his own kind, garrulous with others ... so one might describe the purple sandpiper, and so men describe me ... I can think of many things worse than being likened to you, my feathered Jeremiah, for we have both crawled from the hand of the same craftsman, been carved with the same knife: you quickened to life on the fourth day, I on the sixth ... But what if the order had been reversed?"

Purple sandpiper (Calidris maritima). Photo: Ron Knight (licensed under CCA).

"The island rises ... it emerges from the deep as the flood tide strips the water from its shores ... Fish flee the dry land, out to the dark depths ... Shore birds, newly arrived, follow the ebbing tide, scurrying along the water's edge, pecking around their feet ... The tide mark retreats rapidly, like a silk glove drawn off a maiden's hand ... A bank of liver-coloured seaweed glitters in the morning sun, swollen and vulnerable ... Ever more is revealed of the black bedrock on which the island sits."

"The days now passed in discourse of runes and old Icelandic poetry. Ole Worm placed many riddles before Jonas on the Eddic and Skaldic compilations of Snorri Sturluson, which he was able to answer straight off ... But the university rector had other duties to attend to besides tapping Jonas's wisdom, and this gave the latter the chance to observe the work in Worm's collection of natural history and curiosities, known as the Museum Wormianum ... An elite team of the rector's students was busy cataloguing the collection ... Here Jonas set eyes for the first time on many marvels he had hitherto only read about in books ... "

Mark Patton's novels, Undreamed Shores, An Accidental King and Omphalos, are published by Crooked Cat Publications, and can be purchased from Amazon UK or Amazon USA.

Thursday 12 March 2015

A History of the World in 50 Novels. 23 - "John Saturnall's Feast," by Lawrence Norfolk

"Had I desired to foment trouble," Martin Luther declared in a sermon, "I could have brought great bloodshed upon Germany." His remarks were, in part, directed against one of his own supporters, Andreas Karlstadt who, in his absence from Wittenberg, had unleashed a series of iconoclastic riots on the churches of the city. Luther's own desire for peaceful and lawful reform of the church was sincerely felt, but the Reformation he set in motion, aided by Gutenberg's printing press, would be far from bloodless.

As the Catholic Church's monopoly over the souls of Europe's Christians crumbled, with it fell all the certainties on which Medieval life had been based. If the only ultimate truths were to be found in scripture, as Luther believed, and if each man and woman could read the scriptures in his or her own language, then each might have his or her own interpretation of it. Between 1520 and 1620, a whole host of loosely "Protestant," but, in fact widely disparate religious cults established themselves across Europe: Presbyterian, Anabaptist, Hussite, Adamite, Arminian, Puritan.

The "Catalogue of Sects" - English broadsheet of 1647, British Museum (image is in the Public Domain).

The arrest of Adamites in Amsterdam. Adamites believed in "Holy Nudity," and held their wives in common. Image: Wellcome Trust (reproduced with permission).

The influence was not only religious, but also political, for if kings did not rule by divine right, mediated through the institutions of "One Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church," then by what right did they rule?

John Saturnall's Feast is set in a fictional vale in Somerset, and spans the period before, during and immediately after the English Civil War. It follows the progress of John Sandall (or Saturnall) who, with his mother as a boy, is hounded out of his village by the Puritans who have taken control, under the menacing presence of the fanatical Timothy Marpot. They take refuge in the woods, where John's mother starves to death. A clergyman takes pity on the boy and sends him to Buckland Manor, where he is taken on as an apprentice in the kitchens.

The Jacobean kitchens at Ham House, on which Lawrence Norfolk styled the kitchens of the fictional Buckland Manor. Photo: National Trust (image is in the Public Domain).

As we follow John in his apprenticeship, we learn a good deal about 17th Century cookery, much of it based on a contemporary book of recipes from the kitchen of Sir Kenelm Digby (himself a minor character in the novel). Some of the recipes are included, although "Wild Boar a la Troyenne" is not one that I will attempt in the kitchen of my writer's garret!

When Charles I raises his banner at Nottingham in 1642, John finds himself cooking for the Royalist Army, marching from camp to camp until the final defeat at Naseby in 1645. Then he and his comrades must make their way home, and rebuild their lives as best they can.

Royalist musketeers & pike-men in a re-enactment of the Battle of Naseby. English Heritage Festival of History 2005. Photo: Gene Arboit (licensed under GNU).

In this novel we see the great events of history through the eyes not of its architects, but of ordinary people whose concern is with survival. On the battlefield, John Saturnall proves himself braver than some of his social "betters," but his loyalty is to his companions more than to an abstract political or religious ideal. At times dark and at others joyous, it is a story of survival in an age when religious fundamentalism tore or own land apart, as it now rages through Syria and Iraq.

"John boiled, coddled, simmered and warmed. He roasted, seared, fried and braised. He poached stock-fish and minced the meats of smoked herrings while Scovell's pans steamed with ancient sauces: black chawdron and bukkenade, sweet and sour egredouce, camelade and peppery gauncil. For the feasts above he cut castellations into pie-coffins and filled them with meats dyed in the colours of Sir William's titled guests. He fashioned palaces from wafers of spiced batter and paste royale, glazing their walls with panes of sugar. For the Bishop of Carrboro they concocted a cathedral."

"The Chef," unknown artist of the 17th Century. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (image is in the Public Domain).

"The latest encampment of the Buckland Kitchen was a roofless barn on a rise overlooking the valley below. Spread out over the fields, the troops of the King's army gathered around their fires. The smells of woodsmoke and latrines drifted up the shallow slope ... They had all learned new skills, John reflected. Even the cooks. Scavenging meals from hedgerows, snaring rabbits, finding firewood and shelter in the midst of downpours."

"Harsh shouts echoed in the servants' yard then the nearest cooks shuffled aside. A man garbed in black breeches, a plain black smock, black jacket and short black cloak entered. In one hand he carried a Bible. The other held the bell ... All that remained of the altar was a rectangular scar on the floor. The glass had been smashed from the windows and the bare walls whitewashed ... Buckland's new pastor cast his eyes over the Household, threw his arms wide and sent his cloak flapping like the wings of a monstrous crow."

Mark Patton's novels, Undreamed Shores, An Accidental King, and Omphalos, are published by Crooked Cat Publications, and can be purchased from Amazon UK or Amazon USA. Omphalos is on the long-list for the M.M. Bennetts Prize for Historical Fiction.

As the Catholic Church's monopoly over the souls of Europe's Christians crumbled, with it fell all the certainties on which Medieval life had been based. If the only ultimate truths were to be found in scripture, as Luther believed, and if each man and woman could read the scriptures in his or her own language, then each might have his or her own interpretation of it. Between 1520 and 1620, a whole host of loosely "Protestant," but, in fact widely disparate religious cults established themselves across Europe: Presbyterian, Anabaptist, Hussite, Adamite, Arminian, Puritan.

The "Catalogue of Sects" - English broadsheet of 1647, British Museum (image is in the Public Domain).

The arrest of Adamites in Amsterdam. Adamites believed in "Holy Nudity," and held their wives in common. Image: Wellcome Trust (reproduced with permission).

The influence was not only religious, but also political, for if kings did not rule by divine right, mediated through the institutions of "One Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church," then by what right did they rule?

John Saturnall's Feast is set in a fictional vale in Somerset, and spans the period before, during and immediately after the English Civil War. It follows the progress of John Sandall (or Saturnall) who, with his mother as a boy, is hounded out of his village by the Puritans who have taken control, under the menacing presence of the fanatical Timothy Marpot. They take refuge in the woods, where John's mother starves to death. A clergyman takes pity on the boy and sends him to Buckland Manor, where he is taken on as an apprentice in the kitchens.

The Jacobean kitchens at Ham House, on which Lawrence Norfolk styled the kitchens of the fictional Buckland Manor. Photo: National Trust (image is in the Public Domain).

As we follow John in his apprenticeship, we learn a good deal about 17th Century cookery, much of it based on a contemporary book of recipes from the kitchen of Sir Kenelm Digby (himself a minor character in the novel). Some of the recipes are included, although "Wild Boar a la Troyenne" is not one that I will attempt in the kitchen of my writer's garret!

When Charles I raises his banner at Nottingham in 1642, John finds himself cooking for the Royalist Army, marching from camp to camp until the final defeat at Naseby in 1645. Then he and his comrades must make their way home, and rebuild their lives as best they can.

Royalist musketeers & pike-men in a re-enactment of the Battle of Naseby. English Heritage Festival of History 2005. Photo: Gene Arboit (licensed under GNU).

In this novel we see the great events of history through the eyes not of its architects, but of ordinary people whose concern is with survival. On the battlefield, John Saturnall proves himself braver than some of his social "betters," but his loyalty is to his companions more than to an abstract political or religious ideal. At times dark and at others joyous, it is a story of survival in an age when religious fundamentalism tore or own land apart, as it now rages through Syria and Iraq.

"John boiled, coddled, simmered and warmed. He roasted, seared, fried and braised. He poached stock-fish and minced the meats of smoked herrings while Scovell's pans steamed with ancient sauces: black chawdron and bukkenade, sweet and sour egredouce, camelade and peppery gauncil. For the feasts above he cut castellations into pie-coffins and filled them with meats dyed in the colours of Sir William's titled guests. He fashioned palaces from wafers of spiced batter and paste royale, glazing their walls with panes of sugar. For the Bishop of Carrboro they concocted a cathedral."

"The Chef," unknown artist of the 17th Century. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (image is in the Public Domain).

"The latest encampment of the Buckland Kitchen was a roofless barn on a rise overlooking the valley below. Spread out over the fields, the troops of the King's army gathered around their fires. The smells of woodsmoke and latrines drifted up the shallow slope ... They had all learned new skills, John reflected. Even the cooks. Scavenging meals from hedgerows, snaring rabbits, finding firewood and shelter in the midst of downpours."

"Harsh shouts echoed in the servants' yard then the nearest cooks shuffled aside. A man garbed in black breeches, a plain black smock, black jacket and short black cloak entered. In one hand he carried a Bible. The other held the bell ... All that remained of the altar was a rectangular scar on the floor. The glass had been smashed from the windows and the bare walls whitewashed ... Buckland's new pastor cast his eyes over the Household, threw his arms wide and sent his cloak flapping like the wings of a monstrous crow."

Mark Patton's novels, Undreamed Shores, An Accidental King, and Omphalos, are published by Crooked Cat Publications, and can be purchased from Amazon UK or Amazon USA. Omphalos is on the long-list for the M.M. Bennetts Prize for Historical Fiction.

Sunday 8 March 2015

Versatile Bloggers - Introducing some of my favourite blogs

My friend and fellow author, Alison Morton, has nominated me as a versatile blogger. It’s a way to recognise other bloggers and introduce them and their readers to new blogs. And people blog about the most amazing subjects…

So, what do I have to do?

1. Display the logo (cut and paste it from her post)

2. Write a post and link back to the blogger who nominated me

3. Post seven interesting things about myself (am I that interesting?)

4. Nominate up to fifteen other bloggers (and why I’ve nominated them)

5. Inform them of their nomination

Seven things about me:

1. I am distantly related to the American World War II commander, General George S. Patton. We are both descended from a family of Scottish plantation-men, settled in Ulster by James I.

General George S. Patton with two other officers. Photo: Franklyn D. Roosevelt. US National Archives & Records Administration (reproduced with permission).

2. At school, I had a range of interests that others regarded as eccentric, and one of these was ornithology (bird-watching). Birds feature as minor characters in all of my novels, with different species in each one (golden orioles & great bustards in Undreamed Shores, a raven in An Accidental King, short-toed tree-creepers and wall-creepers in Omphalos).

Great bustards, now reintroduced to Salisbury Plain. Photo: Great Bustard Group (licensed under CCA).

3. As a teenager, I did a great deal of sailing between the Channel Islands, Normandy and Brittany. I crewed for other people, never owning my own boat, but I could not have written Undreamed Shores without the knowledge and experience I gained.

4. My earliest ambition was to be an RAF fighter pilot, but discovered, during a couple of years as a cadet, that I had absolutely none of the necessary skills or aptitudes.

5. I studied archaeology at Cambridge, and had an 18-year archaeological career. I had published more than a million words of academic prose before I turned my attention to fiction, but my latest novel, Omphalos, draws directly on my excavations at La Hougue Bie, on the island of Jersey.

La Hougue Bie, Jersey (licensed under CCA).

6. I contested the 1997 parliamentary election as Labour candidate for Lewes. It was arguably the worse-timed dress rehearsal in recent parliamentary history, although I'm sure I wasn't the only one to make that mistake.

7. I was an academic dean for 9 years at the University of Westminster, during which time I helped to set up a great many international projects, including a new university in Uzbekistan. My experience of leadership has certainly informed my novels (most especially An Accidental King), but I'm not allowed to spill too many beans when it comes to the specific incidents that informed particular scenes.

Now on to my favourite blogs. My next novel, like Omphalos, has storylines set in different periods, so I follow a diverse array:

Nancy Jardine writes novels set in northern Britain at the time of the Roman conquest, blogs about the background to these, as well as hosting guest-posts with other authors.

E.M. Powell writes novels set in the High Middle Ages, and blogs about the background to them, and about a range of historical and historical fiction topics.

Madame Gilflurt focusses on 18th Century Britain, and is a goldmine of information.

Dr Caitlin Green is an academic who specialises in the archaeology and history of Early Medieval England, but who blogs on a much wider range of topics.

English Historical Fiction Authors is a collective of historical fiction authors, of which I am one, and between us we cover a different topic every day, ranging from prehistory to the 20th Century.

The History Girls is a similar collective which, for obvious reasons, I'm not eligible to join, but which covers a similarly broad and interesting range of topics.

Decoded Past offers informative posts on all aspects of world history and archaeology.

Spitalfields Life focusses specifically on the history of London and, since this is what I am currently researching, I follow it closely.

Peirene Press is (alongside Crooked Cat, which publishes my own novels) one of my favourite small publishers. They acquire the English language rights to the finest short fiction titles published in other European languages, and then employ some of the best literary translators in the world to make them available to an Anglophone readership.

Mark Patton's novels, Undreamed Shores, An Accidental King and Omphalos, are published by Crooked Cat Publications, and can be purchased from Amazon UK or Amazon USA.

So, what do I have to do?

1. Display the logo (cut and paste it from her post)

2. Write a post and link back to the blogger who nominated me

3. Post seven interesting things about myself (am I that interesting?)

4. Nominate up to fifteen other bloggers (and why I’ve nominated them)

5. Inform them of their nomination

Seven things about me:

1. I am distantly related to the American World War II commander, General George S. Patton. We are both descended from a family of Scottish plantation-men, settled in Ulster by James I.

General George S. Patton with two other officers. Photo: Franklyn D. Roosevelt. US National Archives & Records Administration (reproduced with permission).

2. At school, I had a range of interests that others regarded as eccentric, and one of these was ornithology (bird-watching). Birds feature as minor characters in all of my novels, with different species in each one (golden orioles & great bustards in Undreamed Shores, a raven in An Accidental King, short-toed tree-creepers and wall-creepers in Omphalos).

Great bustards, now reintroduced to Salisbury Plain. Photo: Great Bustard Group (licensed under CCA).

3. As a teenager, I did a great deal of sailing between the Channel Islands, Normandy and Brittany. I crewed for other people, never owning my own boat, but I could not have written Undreamed Shores without the knowledge and experience I gained.

4. My earliest ambition was to be an RAF fighter pilot, but discovered, during a couple of years as a cadet, that I had absolutely none of the necessary skills or aptitudes.

5. I studied archaeology at Cambridge, and had an 18-year archaeological career. I had published more than a million words of academic prose before I turned my attention to fiction, but my latest novel, Omphalos, draws directly on my excavations at La Hougue Bie, on the island of Jersey.

La Hougue Bie, Jersey (licensed under CCA).

6. I contested the 1997 parliamentary election as Labour candidate for Lewes. It was arguably the worse-timed dress rehearsal in recent parliamentary history, although I'm sure I wasn't the only one to make that mistake.

7. I was an academic dean for 9 years at the University of Westminster, during which time I helped to set up a great many international projects, including a new university in Uzbekistan. My experience of leadership has certainly informed my novels (most especially An Accidental King), but I'm not allowed to spill too many beans when it comes to the specific incidents that informed particular scenes.

Now on to my favourite blogs. My next novel, like Omphalos, has storylines set in different periods, so I follow a diverse array:

Nancy Jardine writes novels set in northern Britain at the time of the Roman conquest, blogs about the background to these, as well as hosting guest-posts with other authors.

E.M. Powell writes novels set in the High Middle Ages, and blogs about the background to them, and about a range of historical and historical fiction topics.

Madame Gilflurt focusses on 18th Century Britain, and is a goldmine of information.

Dr Caitlin Green is an academic who specialises in the archaeology and history of Early Medieval England, but who blogs on a much wider range of topics.

English Historical Fiction Authors is a collective of historical fiction authors, of which I am one, and between us we cover a different topic every day, ranging from prehistory to the 20th Century.

The History Girls is a similar collective which, for obvious reasons, I'm not eligible to join, but which covers a similarly broad and interesting range of topics.

Decoded Past offers informative posts on all aspects of world history and archaeology.

Spitalfields Life focusses specifically on the history of London and, since this is what I am currently researching, I follow it closely.

Peirene Press is (alongside Crooked Cat, which publishes my own novels) one of my favourite small publishers. They acquire the English language rights to the finest short fiction titles published in other European languages, and then employ some of the best literary translators in the world to make them available to an Anglophone readership.

Mark Patton's novels, Undreamed Shores, An Accidental King and Omphalos, are published by Crooked Cat Publications, and can be purchased from Amazon UK or Amazon USA.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

_F0173k.jpg)

_(13668127544).jpg)